Original story written by Sean McNeely and published on A&S News.

Titilola Aiyegbusi is studying the life writing of Black Canadian women to understand how their stories about culture, belonging, and collective memory have shaped — and continue to shape — Black identity and consciousness in Canada.

“This topic has not received much academic attention in the past, so I’m coming in to lay the foundations of the critical perspective to these works,” says Aiyegbusi, a PhD candidate in the Faculty of Arts & Science’s Department of English. “My primary source materials are autobiographies, memoirs, letters, diaries, interviews, and anything that documents Black Canadian women’s lived experiences.”

Many of the works she studies aren’t easy to find. There’s a lot of research, visiting archives, searching on Amazon for lone copies of books, and spending time at the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library.

Her research spans literature written long before Canada was a country, with the earliest work being the court transcripts of Marie-Joseph Angélique — an enslaved woman who was accused of burning down Montreal in 1734.

Angélique was found guilty of setting fire to her enslaver’s home, which led to the destruction of much of what is now Old Montreal. However, the evidence against her was purely circumstantial, and she consistently maintained her innocence throughout the trial. Today, many historians argue that her conviction was likely influenced more by her reputation as a rebellious runaway than by any solid evidence.

“It’s the text that begins Black Canadian women's life narratives,” says Aiyegbusi.

At what point did Black Canadian women start putting their experiences in print, and are there ways in which their writing fits or departs from how we conceive life writing as a genre?

What’s her goal for examining these works?

“There are two aspects to it,” she says. “One is in mapping the field itself — how have Black Canadian women written about their lives? What are the conditions that prompted the writing of their lives, and what are the prevalent themes in their works?”

She also examines the theory of life writing and suggests that the definition of this genre could be broadened when considering factors such as how Black women had limited access to printing and publishing, as well as an exclusion from education.

“How did that impact life writing?” she asks. “At what point did Black Canadian women start putting their experiences in print, and are there ways in which their writing fits or departs from how we conceive life writing as a genre?”

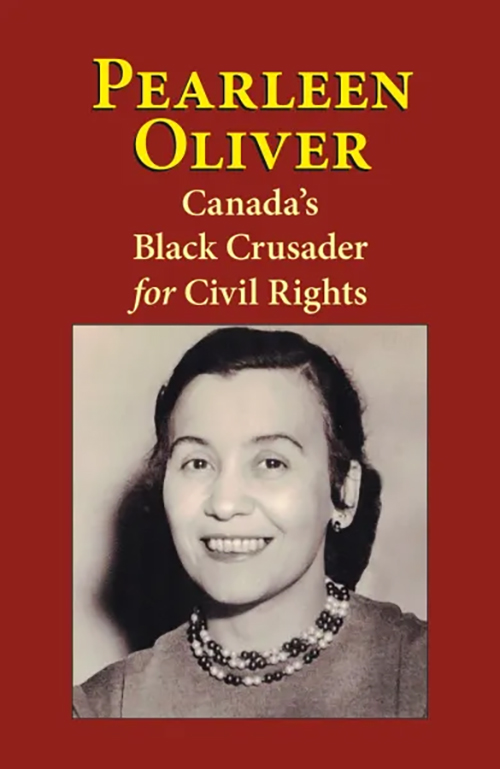

One example of this is the autobiography of Pearleen Oliver (1917–2008) titled Pearleen Oliver: Canada's Black Crusader for Civil Rights.

Oliver was an anti-Black racism activist, writer, historian and educator. Among her accomplishments, she founded the Nova Scotia Association for the Advancement of Coloured People and advocated against the exclusion of Black students from nursing, and against racial segregation in schools.

Thanks to her efforts, in 1945, two Black nurses were admitted into maternity nursing school for the first time in Canada’s history. “We celebrate these two women but tend to forget that it was Oliver who facilitated that access,” says Aiyegbusi.

Oliver’s story was later written posthumously as an autobiography, published from archival documents, interviews she granted, newspaper articles she published, and interviews from her friends and family.

Through her research, Aiyegbusi is committed to showcasing stories like Oliver’s, feeling that we don’t have to look south of the border to find powerful tales of Black people overcoming racism.

“We tell the story of Rosa Parks, Martin Luther King and Sojourner Truth, but we forget that there were Black people here in Canada who struggled against oppression as well,” she says. “We don't have to look elsewhere for stories of Black excellence. We have them right here.”

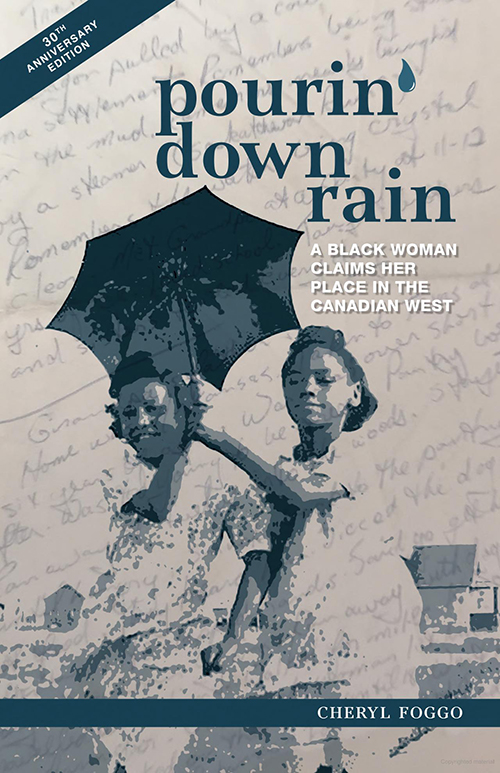

For example, she encourages students and faculty to consider reading books like Cheryl Foggo’s memoir, Pourin’ Down Rain: A Black Woman Claims Her Place in the Canadian West.

“It discusses the history of Black people in the prairies,” says Aiyegbusi. “Using the story of her family that spans four generations, she explores the issues of racial identity and belonging as she unravels the discrimination that Black pioneers grappled with as they settled into western Canada. It’s a good book for anyone trying to understand what it means to be Black in a predominately white space.”

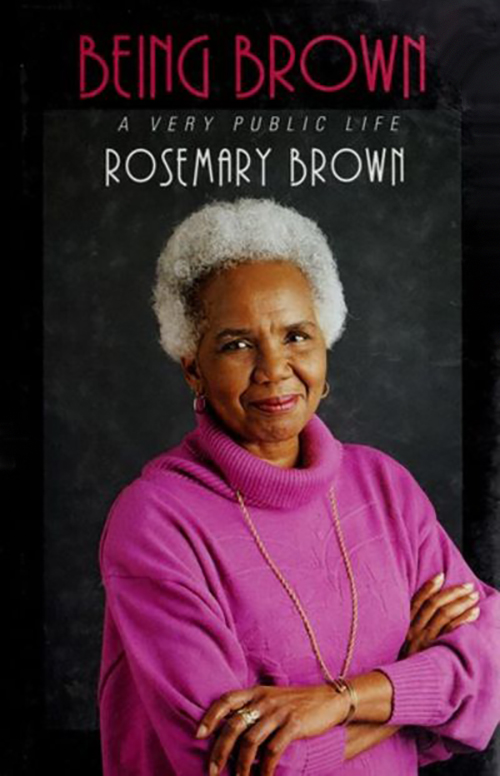

She also highly recommends Rosemary Brown’s autobiography, Being Brown: A very Public Life.

“I recommend this autobiography for anyone interested in the intersection of politics and feminism in Canada,” says Aiyegbusi.

“Brown's radical stance on women's rights and racial issues marked a turning point in the history of Canadian politics as she openly scrutinized the conditions that made it possible to discriminate against women and visible minorities. Being Brown isn’t just a polemic against sexism and racism, it is also a radical stand on socialism, one that sees feminist ideals as an integral aspect of a socialist system.”

Aiyegbusi’s decision to explore these books and other Black Canadian women life writing stems from her own experiences.

Between completing her master’s degree at the University of Lethbridge and starting her PhD at U of T, there was a gap of four years where she worked as a financial advisor in Alberta.

“Some of the things I experienced started keeping me awake at night,” she says. “When you hear something or see something that causes you discomfort, you want to talk back to it, but I just couldn't find the words to speak to the situations I experienced. I felt if I talked, I would be walking into the trap of being stereotyped as an angry Black woman.

“So, I kept my peace; yet I had no peace. I realized that I had to find a way to speak back to this kind of racism. But to speak back to racism, you really need precise words that are clear, words that frame your argument well within the delicate context of past and current socio-political discourse. I realized I lacked the broader context that inspires such words, so I decided it was time to go back to school.”

Since making that decision, each work she studies provides unexpected gifts.

“There’s always something surprising every time you read life narratives,” she says. “You realize how our lived experiences have been impacted by the hard work of those who have gone ahead of us.”